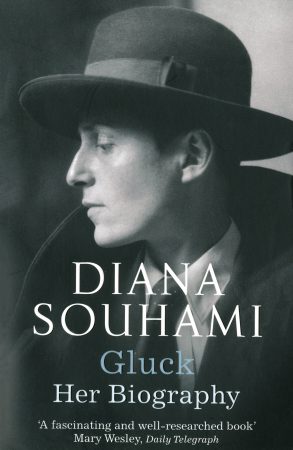

Her Biography

Quercus · 336 pp · 1988

She was born Hannah Gluckstein in 1895 into the family that founded the J. Lyons & Co. catering firm. She had passionate affairs with society women, chose her own monosyllabic name and only exhibited her paintings in ‘one man’ shows. Her torrid personal life shocked her family, though the money she received from them allowed her to live in style. In the 1920s and ’30s Gluck’s portraits, flower paintings and landscapes, set in frames she designed and patented, were coveted by the rich and famous. At the height of her fame she stopped working, caught in a bitter campaign over the quality of artists’ materials. Then, when nearly eighty, she returned to the limelight with a burst of creative energy. In this book Diana Souhami interweaves the pictures, people and events that made up Gluck’s life.

I saw a retrospective of Gluck’s paintings one rainy lunchtime. YouWe, as she called it, a self-portrait of her head fused with that of her lover Nesta Obermer, intrigued me. Here was obsession, lesbian love, merged identity.

D.S.

UK: Hive · Foyles · Waterstones · amazon · Kindle

US: IndieBound · BAM · Powells · amazon · Kindle

Read an excerpt

‘Gluck: No Prefix, No Quotes’

On the backs of photographic prints of her paintings, sent out for publicity purposes, she always wrote in her elegant handwriting ‘Please return in good condition to Gluck, no prefix, suffix or quotes.’ She pronounced her chosen name with a short vowel sound to rhyme with, say, cluck or duck. She was born Hannah Gluckstein in 1895 into the family that founded the J.Lyons and Co. catering empire, but seldom wanted her wealthy family connections or hated patronymic known.

To Nesta Obermer, her blonde alter ego in ‘Medallion’, a painting of their merged profiles, she was ‘Darling Tim’ or ‘my bestest darling Timothy Alf’ or ‘My Black Brat’. Romaine Brooks, twenty years her senior, did a portrait of her in 1924 called ‘Peter – a Young English Girl’. To one at least of her admirers she was ‘Dearest Rabbitskinsnootchbunsnoo’. To Edith Shackleton Heald, the journalist with whom she lived for close on forty years, she was ‘Dearest Grub’. To her family she was ‘Hig’. To her servants and the tradespeople she was Miss Gluck and to the artworld and in her heart she was simply Gluck.

The reason she gave for choosing to be known by this austere monosyllable was that the paintings mattered not the sex of the painter. She said she thought it sensible to follow the example of artists like Whistler and use a symbol by way of identification. More fundamentally, she had no inclination to conform to society’s expectations of womanly behaviour and she wanted to sever herself, but not entirely, from her family.

Gluck she was, and could and did become high-handed and litigious in so being. Many were confused and bewildered as to how to address her with courtesy. She had an irritated exchange with her bank when an unwitting clerk fed her name into the computer as Miss H. Gluck. A graphic designer, faced with the uncomfortable visual dilemma of trying to make GLUCK look comprehensible on the letterhead of stationery for an art society which featured her, along with the Bishop of Chichester and Duncan Grant as it Vice Presidents, stuck in an ameliorating Miss. Gluck resigned and insisted on the inking out of her name. When Weidenfeld & Nicolson published a minor novel, which featured an eccentric vagabond, called Glück with an umlaut who lived in a lodging house and painted pictures of bus tickets and defunct clocks, they found themselves besieged with solicitor’s letters. Gluck regarded any encroachment on her chosen name as trespass liable for prosecution.

Throughout her adult life she dressed in men’s clothes, pulled the wine corks and held the door for true ladies to pass first. An acquaintance seeing her dining alone remarked that she looked like the ninth Earl, a description that she liked. She had a last for her shoes at John Lobb’s the Royal bootmakers, got her shirts from Jermyn Street, had her hair cut at Truefitt gentlemen’s hairdressers in Old Bond Street and blew her nose on large linen handkerchiefs monogrammed with a G. In the early decades of the twentieth century, when men alone wore the trousers, her appearance made heads turn. Her father, a conservative and conventional man was utterly dismayed by her ‘outré clobber’, her mother referred to a ‘kink in the brain’ which she hoped would pass, and both were uneasy at going to the theatre in 1918 with Gluck wearing a wide Homburg hat and long blue coat, her hair cut short and a dagger hanging at her belt.

She did several self-portraits all of them mannish. There was a jaunty and defiant one in beret and braces – stolen in 1981 – and another, now in the National Portrait Gallery, which shows her as arrogant and disdainful. She painted it when suffering acutely from the tribulations of love. A couple of others she destroyed when depressed about her life.

She dressed as she did not simply to make her sexual orientation public, though that of course she achieved. By her appearance she set herself apart from society, alone with what she called the ‘ghost’ of her artistic ambition. And at a stroke she distanced herself from her family’s expectations, which were that she should be educated and cultured but pledged to hearth and home. They would have liked her to marry well, which meant a man from a similar Jewish background to hers – preferably one of her cousins – and to live, as wife and mother, a normal happy life. By her ‘outré clobber’ Gluck said no to all that for who in his right mind would court a woman in a man’s suit. Her rebelliousness cut her father to the quick and he thought it a pose. But however provocative her behaviour there was no way he would cease to provide for her, his concept of family loyalty and obligation was too strong.

Courtesy of her private income she lived in style with staff – a housekeeper, cook and maids – to look after her. She always kept a studio in Cornwall. In the 1920s and 30s she live in Bolton House, a large Georgian house in Hampstead village. After the war she settled in the Chantry House Steyning with Edith Shackleton Heald, journalist, essayist and lover of the poet W.B.Yeats in his twilight years. Both residences had elegantly designed detached studios.

Her portraits of women are among her best work. The national art galleries house an abundance of reclining nudes but not many portraits of women by women. Gluck’s women wear their hats, jewellery and clothes to show their self-assurance, assertiveness, status and style. Her portrait of Molly Mount Temple, at one of whose glittering party weekends at Broadlands Gluck met the love of her life is a study in arrogance and disdain: arms akimbo, her hat and aquamarines badges of status and power, her lips and nails bright red and an M for Molly and Mount Temple engraved on the buckle of her belt.

In the 1920s when the world was dancing mad, when every restaurant in town had a floorshow and C.B.Cochran’s reviews were a showcase for theatrical talent, Gluck went again and again to the London Pavilion advertised as ‘The Centre of the World’ to paint scenes from the most popular of his shows, On with the Dance. In the thirties, when she had an affair with Constance Spry, she painted formal arrangements of flowers in ornate vases. Fashionable interior designers, Oliver Hill, Syrie Maugham, Norman Wilkinson, hung her paintings in rooms they designed. In the war years Gluck captured the spirit of the home front in pictures of soldiers playing snooker, or the firewarden’s office at one in the morning. In her last years, when she was beached, lost and lonely, that was what her painting showed: a lone bird flying into the sunset, waves washing in on a deserted shore, an iridescent fish head washed up by the tide.

Like Mondrian she tried to see her paintings as part of an architectural setting. She designed and patented a frame, which bears her name. It consisted of three symmetrically stepped panels painted the same colour as the wall on which it was hung or covered in the same paper. The effect was to incorporate the picture into the wall. She patented it in 1932 and used it in all subsequent exhibitions to create what became known as ‘The Gluck Room’, the total architectural effect of paintings and their setting.

Her private income meant she was not driven to earn her living from work. She painted only what she chose. She disliked commercialism, easy production and the second-rate in art: ‘I made a vow that I would never prostitute my work and I never have… Never, never have I attempted to earn my bread at the cost of my work.’ She had too grand ideas of Time and Vision and her own genius. She was capable of spending three years on a picture then destroying it if she felt it to be no good.

When young she felt her life was charmed. Aged forty-one she fell in love and thought it would last forever. In essence she was a romantic optimist and when Love ‘to all Eternity’ failed her, as in the 1940s Love did, because it had no pragmatic base, she locked into sorrow with the tenacity she brought to work or pleasure. The failure of love crippled her self-regard, made her deny herself the consolation of work and behave in a destructive way toward those who sought to help her.

Obsession was her fatal character flaw. At its best it supported her perfectionism – an absolute dedication and commitment to each of her paintings. At its most wasteful it caused her to ‘campaign’ on issues which she always regarded as important but which consumed her time, energy and focus. The great battle that kept her from her easel was over the quality of artists’ materials. It became known as her ‘paint war’. She fought it with the paint manufacturers, the British Standards Institution and, it seemed, the world at large, for more than a decade – from 1953-1967.

Gluck wanted to be remembered for her paintings, the investigation she instigated into the quality of artists’ materials and setting of a British Standard for oil pigments and the stepped frame she designed. She also wanted her life remembered, problematic though it was. She was, more than most, full of paradoxes and contradictions. ‘You couldn’t,’ said Winifred Vye her housekeeper in old age, ‘say anything absolutely bad about her because then she’d confound you and be nice… She was just extremely difficult to live with.’

She was proud, authoritative, obsessive and egotistical yet dependent in every domestic sense and humble about her work. She was a romantic and yet spent years in an arid campaign about the quality of paint. She felt herself to be a visionary painter and yet some of the best of her work was done to commission for the walls of the sophisticated and rich. She claimed that she ran away from her family, but she kept half their name and was always dependent on them financially. She was a rebel and a misfit but staunchly patriotic, politically conservative and good friends with several high court judges including the Master of the Rolls. She was a Jew but wanted to pain the crucifixion of Christ. She was a woman but she dressed as a man. She would call the kitchen staff to account if the housekeeping was a halfpenny out, then give a mere acquaintance £500 to buy a new typewriter. She wanted for nothing in a material sense and yet allowed herself to be consumed by material concerns. She was unafraid of death and yet hypochondriacal.

Mercurial, maddening, conspicuous and rebellious, she inspired great love and profound dislike. Perhaps what she most feared was indifference – the coldest death. Her dedication to work was total, even through her fallow years. Her severance from gender, family and religion, her resistance to influence from any particular artist or school of painting, her refusal to exhibit her work except in ‘one-man’ shows were all ways of protecting her artistic integrity. She desired to earn her death through the quality of her work: ‘I do want to reach that haven having a prize in my hand… Something of the trust that was reposed in me when I was sent out…’ In reaching her destination with her paintings as her prize she took a circuitous path – unmapped, thorny and entirely her own.

Praise for Gluck

Diana Souhami has written a fascinating and well-researched book about this remarkable woman and important artist, who dressed as a man and painted in her own unique style. She has caught Gluck’s mania for excellence and the passion she spent on her lovers.

Mary Wesley · Daily Telegraph

A quiet triumph.

Ruth Jarvis · Publishing News

Exquisite… full of psychological depth.

Terry Castle · Author of The Literature of Lesbianism

Souhami tells Gluck’s bizarre story with sympathy, unsensational frankness, and a gusto laced with civilised irony.

John Russell Taylor · Times

A fine balance of revelation and restraint which chronicles a live characterised by intense feeling and (as Diana Souhami quietly admits) a lot of bad behaviour.

Janet Watts · Observer