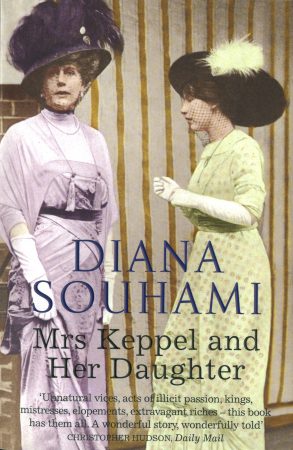

Quercus · 376 pp · 1996

Alice Keppel, lover of Queen Victoria’s son Edward VII and great-grandmother of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, was the acceptable face of Edwardian adultery. It was her art to be the king’s mistress yet to laud the Royal Family and the institution of marriage. She partnered the king for yachting at Cowes and helped him choose presents for his wife, Queen Alexandra while remaining calmly married to her complaisant husband George.

But for her daughter Violet, passionately in love with Vita Sackville-West, romance proved tragic and destructive. Mrs Keppel used all the force at her command to suppress their affair. This fascinating and intense mother-daughter relationship highlights Edwardian and contemporary duplicity and double standards and goes to the heart of the questions about monarchy, family values and sexual freedoms.

Hypocrisy is the core of Mrs Keppel and Her Daughter. Mrs Keppel, as mistress of King Edward VII, was ‘La Favorita’ of Edwardian high society. Her daugher Violet Trefusis was ostracised, forced into a sham marriage and banished to Paris because of her stormy love affair with Vita Sackville-West.

D.S.

UK: Hive · Foyles · Waterstones · amazon · Kindle

US: IndieBound · BAM · Powells · amazon · Kindle

Read an excerpt

Portrait of a Lesbian Affair

Violet arrived at the Paris Ritz with her husband and maid on the evening of Tuesday 17 June. Her honeymoon was to last a month. She wore new clothes but no wedding ring. Mrs Keppel had supervised her trousseau: a satin peignoir trimmed with ostrich feathers, travelling coats with matching hats.

Harold did not keep Vita under lock and key as he’d promised. Tuesday was a working day and he was busy with the Peace Conference. She left Versailles and booked in alone at the Hotel Roosevelt in Paris. On 18 June she met Violet at the Ritz, went back with her to her own hotel and had sex with her. ‘I treated her savagely. I had her. I didn’t care, I only wanted to hurt Denys,’ she wrote. She then assured Violet that, come autumn, they would go away together.

Next day they confronted Denys with facts that were terrible to hear. Violet told him she did not care for him. She had planned to run away with Vita instead of marrying him. Marriage to him was only a cover for this elopement. The plan had gone wrong. Neither she nor Vita made any effort to spare his pain. ‘Don’t you know, you stupid fool, that she is mine in every sense of the word,’ Vita said she wanted to say. Denys went white in the face and looked as if he was going to faint. It was a moment of ghastly awakening. For Violet was not Vita’s in every sense of the word. She was hers in the sense of sexual possession. In the eyes of the world and the law she was Denys’s by the contract of their marriage two days before.

Of all the players in the drama it was Denys who now knew the plot. The true relationship between his wife and Vita was clear. It was not loving friendship as he had perhaps liked to suppose. He had been used, tricked. His marriage was not a marriage at all. He was not going to have the consolation of peace after war. To compound his humiliation, that evening Vita dined alone at the Ritz. Violet, with Denys in tears behind her, watched her from an open window in their suite.

In subsequent letters to Violet he referred again and again to that day. If he had hopes that was when they drained away. He cried but could not find words for the mess. He was a man for whom the expression of emotion was a luxury denied. He was volatile, unsettled and in trauma from the war. This was his chance to define civilian life, he needed help not domestic tragedy.

Vita, her point made, booked out of the Roosevelt. She went for two days to Geneva with Harold and when back in Paris booked in with him at the Majestic Hotel. The reparation of their marriage is well documented.

Violet and Denys began their honeymoon and married life. Their schedule was to spend a week in Paris and then to go south to St Jean de Luz. Violet spent the Paris week crying in the Ritz. She told Denys he got on her nerves and mattered no more than a fly on the wall. Everything she said to him made him wince. She counted the number of cigarettes he smoked and they argued about money. He was devastated and at a loss to know what to do. He agreed that if Vita came on to St Jean de Luz, he would leave them together. But Vita went back to Long Barn to write her poems and to garden. She wrote to Harold, ‘everything is ephemeral but not you’.

In St Jean de Luz the newlyweds took separate rooms in the Golf Hotel and had frequent variations on the following conversation:

Denys: What are you thinking about?

Violet: Vita.

Denys: Do you wish Vita were here?

Violet: Yes.

Denys: You don’t care much about being with men, do you?

Violet: No, I infinitely prefer women.

Denys: You are strange aren’t you?

Violet: Stranger than you have any idea of.

He teamed up with a Basque poacher and went off on mule back to into the mountains to shoot vultures. Alone in the hotel Violet got drunk and talked to the patron about Monte Carlo and being in love. She bought Vita a stone for a ring. She wanted an emerald to signify jealousy but settled for a blue agate ‘exactly the same colour as the most wonderful sapphire’. She asked Vita to wear only her ring and no other and to burn all letters she sent her.

Some days four letters came from Vita. It there was none or only a short one, she felt ‘frenzied’ and suspicious:

If only I knew the truth about you and H! If only I knew for certain that you weren’t playing a double game! … Oh God it is degrading to trust you so little.

At the beginning of July she and Denys moved to the Grand Hotel Eskualduna at Hendaye in the Basses-Pyrenees. ‘Here our rooms aren’t even next door to one another.’ They went for long uncompanionable walks together in the hills. Some days they argued without stopping, on others he was ‘silent, taciturn, unresponsive’. At night Violet wrote to Vita:

O God another whole week of this. It seems I have never wanted you as I do now –

When I think of your mouth…

When I think of other things all the blood rushes to my head and I can almost imagine… If ever anyone was adored and longed for it was you.

In one letter Vita suggested meeting Violet in Italy. Fear of her mother not concern for Denys held Violet back. Mrs Keppel had rented a house for her daughter and son-in-law, Possingworth Manor in Uckfield, Sussex, the tenure of which began on 15 July. ‘Men chinday would be frantic if I didn’t go to the house’ Violet wrote to Vita.

Possingworth Manor was about twenty miles from Long Barn. Denys, still in the army, spent most of the week in London. Violet and Vita spent most of the week with each other. Gossip spread. On 20 July Vita sacked her children’s nanny who spoofed her by walking in the village dressed in a suit of Harold’s.

Violet fought with her mother and pleaded to be released from her marriage. On 21 July she went to bed in tears after an extravagant row:

All this will probably end in my being quite penniless, she already seems to think that I should ‘support myself’ but I won’t, no I won’t let things like being jewel-less and impecunious distress me! … I shall have to become a governess or something!! When I think than men Chinday has at least £20,000 a year.

Denys, a month into marriage, also wanted a separation. He asked Violet to try to give up Vita and burned some of Vita’s letters. His hopes for a workable relationship faded. He said if Violet went abroad with her he would sublet the house, that her parents would have nothing further to do with her and neither would he. Moreover he was ill. He had what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder endured by many who survived the First World War. He also had symptoms of tuberculosis and needed nursing. He was advised to go to Brighton for the sea air. Pat Dansey said Violet would be ‘abysmally selfish’ if she did not go too.

‘Men Chinday,’ with all her genius for society, who excelled in making people happy, needed more than discretion and charm to sort this lot out. This was incoherent feeling, emotional disaster, passion wrecking everything in its path. It needed candid scrutiny, wise disinterested counsel, intervention to avoid more pain. And Mrs Keppel had another worry. Sonia wanted to marry. She was ‘unofficially engaged’ to Roland Cubitt, heir to the Ashcombe title and to the huge building firm founded by his grandfather.

The Cubitts had built much of Belgravia, Pimlico and Eaton Square and had rebuilt Buckingham Palace. Lord and Lady Ashcombe lived at Denbies, Surrey, and were very rich. According to Denys they disapproved of Mrs Keppel’s past relationship with Edward VII and of what they knew of her elder daughter’s heart. They wanted a pretext to squash their son’s marriage. ‘Rolie’ was the fourth in a family of six boys. His three elder brothers died heroes’ deaths in the war. It mattered that he should marry well, fulfil the promise of his brothers, fly the family flag.

The driveway to Denbies was long, the furniture late Victorian, the butler old. In the hall were life-size portraits of Rolie’s dead brothers, a stained glass heraldic window and, in a glass case, part of the skeleton of a brontosaurus. Ladies wore gloves indoors and no one smoked in the drawing room or played cards on Sunday. Lady Ashcombe referred to Sonia in the third person: ‘Will the young lady have a scone?’

Praise for Mrs Keppel and Her Daughter

Both the aristocracy and its double standards about love, marriage and homosexuality have turned out to be remarkably enduring…. Fascinating and richly textured, Souhami’s style is vital, brave and full of flair.

Kennedy Fraser · New York Times

Unnatural vices, acts of illicit passion, kings, mistresses, elopements, extravagant riches – this book has them all. A wonderful story, wonderfully told.

Christopher Hudson · Daily Mail

Souhami uses historical lives to illuminate more than private passions. Funny and precise.

Kathryn Hughes · New Statesman

Souhami has the Midas touch with words. Her narrative sparkles.

Nigel Nicolson · Sunday Telegraph