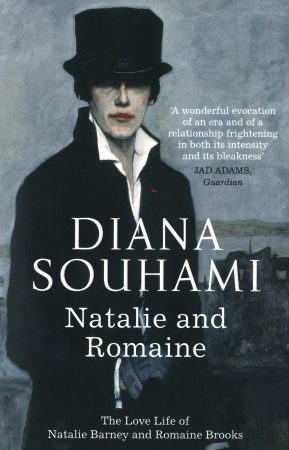

Quercus · 224 pp · 2004

Natalie and Romaine met in London during World War I and their partnership lasted until Natalie died 52 years later. They were both American expatriates; unconventional, energetic, flamboyant and rich.

Natalie was known as ‘the wild girl of Cincinnatti’ and had numerous affairs with other women: Renée Vivien who nailed shut the windows of her apartment, wrote about the loveliness of death, drank eau de cologne and died of anorexia aged 30; and Dolly Wilde niece of Oscar, who ran up terrible phone bills and died of a drugs overdose. Her Friday afternoon salons in the cobbled garden of her Parisian house were for ‘introductions and culture’ and were frequented by Gertrude Stein, Colette, Radclyffe Hall and Edith Sitwell. Romaine achieved fame in her own lifetime and after as an artist. She painted her lovers including Gabriele d’Annunzio with whom she had a terrible and tortured relationship, and the ballerina Ida Rubinstein. However her relationship with Natalie was constant and in their eventful years together they threw up a liberating spirit of culture, style and candour.

Natalie and Romaine was originally published as Wild Girls which was not my choice of title. I’d called my book about Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks, with my own quasi-autobiographical interpolations, A Sapphic Idyll. The marketing men said no one would know what Sapphic meant, particularly the booksellers. I found it hard to say I was the author of Wild Girls and I am happier with Natalie and Romaine. The marketing men still baulk at A Sapphic Idyll.

D.S.

UK: Hive · Foyles · Waterstones · Amazon · Kindle

US: Indiebound · BAM · Powells · Amazon · Kindle

Read an excerpt

Liane de Pougy

‘I have watched women pass by, lit up by their jewellery, like a city at night.’

Liane de Pougy began each day with an enema. It kept her skin clear and her breath sweet, particulars that mattered in her profession. A servant administered it with a syringe and it took a minute or two to work. It was a custom copied from Madame Rhomés, Liane’s mother’s great-aunt, who even at ninety had a complexion like lilies and roses.

Liane took her name from a favoured client, the Comte de Pougy. Titles and the ways of the aristocracy impressed her, especially when allied to money. She viewed lax manners as a moral lapse and was outraged when the poet Max Jacob1 was late for lunch: her asparagus soup had thickened and the risotto had congealed.

She was complimented on the splendour of her jewellery, her fine carriages and inexhaustible wardrobe, her town house in Paris, and lesser houses in Brittany and St Germain. In her prime she employed four Arab servants: a cook, a lady’s maid, a scrubber and a housekeeper and she served peacock foie gras with the champagne.

She spent her mornings in bed. Her dressmaker or milliner might call at midday. On a single visit from Paul Poiret2 she chose fifteen of his designs: a dress in black wool with white embroidery and fringes, another in black silk with organdie flounces, silver tassels and a violet bow, a coat in black and gold with sable collar and cuffs.

Whatever she wore she flirted with it – the moue of her lips against the mesh of a veil, the lifting of her skirt to entice with a leg, the splaying of fingers over the fur at her throat. Such attention to detail and seductive gesture put her above the commonplace. She was of the belle époque, the demi-monde,3 a courtesan not a tart.

She was as voracious for jewels as for clothes. Paris society columns of the 1890s made many a reference to ‘our beautiful Liane de Pougy’, radiant in dazzling white ermine and adorned with pearls. In Kursk in Russia, one of her clients, Count Vladimir Miatleff, ‘a poet and a madman, impotent and a masochist, of the highest nobility, more ancient than the Romanoffs’, summoned a Paris jeweller Jacques Goudstikker to his estate so that Liane might choose a jewel as payment. Goudstikker showed her a ruby and diamond tiara, an emerald necklace, a diamond chain, a parure4 of turquoises and diamonds. Liane could not decide and asked for Miatleff’s help. He told her to take the lot. ‘I took the lot. He was a great nobleman.’

She described herself as vain but not a fool. She cultivated a conversational interest in painting, books and poetry, but avoided depth which she considered dull. Her clients did not pay her to stretch their intellects. She preferred café-concerts and popular songs to Shakespeare or Wagner, and made minor appearances in the chorus of the Folies-Bergere in Paris, in pantomime in St Petersburg and in cabaret clubs in Rome and on the French Riviera.

She was a conscientious bookkeeper, spent five thousand francs without a thought but was careful over five, and said she made all the minor decisions of her life, like marriage, or buying a house, by tossing a coin.

She was born Anne-Marie Chassaigne in 1870 in the Breton city of Rennes. Her mother, a tired-looking woman with large ears, while giving birth hallucinated that St Anne d’Auray, patron saint of the Bretons, prophesied that the child was destined for sainthood. Anne-Marie, even after her metamorphosis into Liane de Pougy, took the prediction seriously. An over-large pearl-encrusted crucifix often bumped below her secular beads.

She had no pleasant memories of childhood as Anne-Marie. To quell curiosity about breasts and vaginas her mother made her wear a chemise in the bath and sold pieces of household furniture to pay for her board at the Convent of the Sacred Heart. AnneMarie abhorred such primness and scrimping and the sight of her father’s worn-out coat and shoes. She became a compulsive pilferer and schemed to escape, to be free and to better herself.

At sixteen she ran away with a sailor, Armand Pourpe. They took lodgings in rue Dragon in Marseilles and their only possession of value was a rosewood piano. They got married when she became pregnant with her son, Marco. She would have preferred the baby to have been a girl ‘because of the dresses and the curly hair’ and was, she said, a terrible mother. ‘My son was like a living doll given to a little girl.’5

‘Events’ and her husband’s bookkeeping drove her, in 1889, into the arms of the Marquis Charles de MacMahon to the agitation of his wife. He was her fourth lover in three years of marriage. The others were a naval lieutenant, a professional gambler, and the Marquis de Portes. When her husband, goaded by such infidelity, shot at her with a revolver and wounded her in the wrist, she advertised the rosewood piano for sale. A young man came to view it, bought it for 400 francs, cash down, and within an hour Anne-Marie was on her way to Paris.

She set up as a courtesan with the Comtesse Valtesse de la Bigne, whose monumental bed was made of varnished bronze. The comtesse was the inspiration for Emile Zola’s Nana, was painted by Edouard Manet, and her seductive success was commemorated in a stained-glass window depicting Napoleon III visiting her in her boudoir. She taught Anne-Marie the profession: money was its goal and life-blood so clients must be rich, she must conceal vulnerability or sentimentality, she must not fear publicity, reproach or blame, or voice principles, morals, or sectarian beliefs. She was to remember that her work put her ‘outside of society and its pettiness’. ‘Don’t be sensitive,’ Valtesse de la Bigne advised.

So Anne-Marie Chassaigne became Liane de Pougy and a shrewd businesswoman. Such kisses, caresses and spasms as she allowed were strictly in exchange for gold. ‘What is your heart? – that thing which beats for the pleasure you expect from me.’ Aspects of her work were disgusting. Many of her clients were intolerably fat, contemptuous of women or unbecomingly peculiar. They paid for fantasy and sexual oddity unavailable at home. They did not ply her with jewels because they liked women, nor was she accommodating because she liked their little ways. Far from it. The essence of the contract was that she served those who could afford her. The organs of Albert, Prince of Wales6 and Maurice de Rothschild7 were royal and rich and more than paid the bills.

Her work at times was demanding: there was ‘a very rich and very ugly Jew’ whose manners she disliked; a ‘silly Bonapartist’ who instructed her to lie waiting for him in a transparent negligee on her polar bear rug, then straddled her and farted; a gambler who smoked fat cigars and paid for her to be exclusively available night and day in a bed at the Grand Hotel Monte Carlo; an unstable, ‘so ugly’ aristocrat, Frédéric de Madrazzo, ‘too nervous, too excited’, who soaked her sheets in sweat… But in payment for a stint she might receive ‘a necklace of the white pearls I love worth one hundred thousand francs’. She accommodated her clients in a Louis XV bed, had more clothes than a bevy of maids could manage, slept in pale blue silk sheets hemmed with lace, and travelled from lord or prince to duke and count with quantities of expensive luggage. And when, on 13 May 1903, her five-row pearl necklace was stolen in rue de la Néva in Paris, her grief was brief. The client bought her another and a platinum ring stuck with diamonds.

1 Max Jacob (1876-1944), writer, poet, painter. In 1909 he had two visions of Jesus Christ, after which, though born a Jew, he converted to Catholicism. He spent much time meditating and praying in the Benedictine Abbey at Saint-Benoit-Sur-Loire. He died in a concentration camp in Draney.

2 Paul Poiret (1879-1944) trained at the House of Worth then set up on his own in 1903. He acted, too. In 1926 he appeared with Colette in La Vagabonde in Monte Carlo.

3 A phrase coined by Alexandre Dumas the younger (1824-95), author of La Dame aux Camélias (1848).

4 A set of jewels to be worn together.

5 Marco Pourpe volunteered as an airman in the First World War. He was killed on 2 December 1914 near Villers-Brettoneux .

6 Liane invited the prince to her debut at the Folies-Bergere: ‘Deign to appear and applaud me and I am made.’ He did and she was.

7 Le Baron Maurice de Rothschild. His waywardness and refusal to work in the family bank alienated him from his father, Edmond.

Praise for Natalie and Romaine

An epic romance, smartly sex-positive and so good-naturedly shocking.

New York Times

Pages are crammed with descriptions of exotic characters, their extravagances and eccentricities, the lilies, the pearls, the velvet-lined rooms…

Selina Hastings · Sunday Telegraph

Her skill, not just in garnering detail but in finding the perfect place for it, is unrivalled.

Jonathan Keates · Literary Review

Souhami is an exceptionally witty and original biographer.

Lucy Hughes-Hallett · Sunday Times

It [has the] kind of honesty – cool, unillusioned, yet also full of emotional subtlety – one yearns for in so much contemporary lesbian writing.

Terry Castle · London Review of Books