I.B. Tauris · 304 pp · 1992

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas were the talk of pre-war Paris. Photographed by Cecil Beaton and Man Ray, painted by Picasso and written about by Hemingway, they were at the heart of Parisian cultural and literary life.

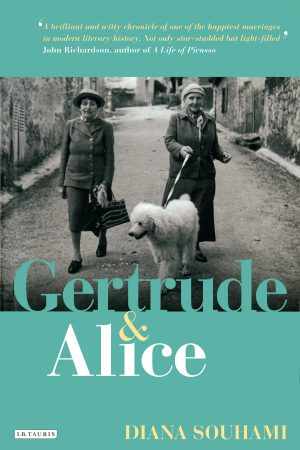

Alice, convinced that Gertrude was a genius, cooked for her, typed her manuscripts and fought to obtain the fame she was convinced Gertrude was due. Alice said Gertrude was the happiest person she had ever known, and was besotted with her for the many years they were together. They were indomitable, charismatic, and wildly eccentric, driving around in ‘Auntie’, their Ford, with Basket, their cherished poodle.

Originally published in 1992, Gertrude and Alice was reissued with a new introduction in 2009.

With Gertrude and Alice I played on the irony that the perfect marriage: loyalty, commitment, delight in each other til death do us part, was between two women. Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, first met in Paris on Sunday 8 September 1907 and from that day on were never apart until Gertrude’s death on Saturday 27 July 1946.

D.S.

UK: Hive · Foyles · Waterstones · amazon · Kindle

US: IndieBound · BAM · Powells · amazon · Kindle

Read an excerpt

Gertrude and Alice

‘In me meeney mine mo.

You are my love and I tell you so’

Gertrude and Alice made a strange-looking pair. In photographs they look like a double act of pontiff and acolyte or Little and Large or a mountain and its shadow. Alice is always carrying the bags and umbrellas or sitting in the lesser chair or walking behind Gertrude or is scarcely visible at all. But she fostered this image of the self-effacing maidservant and it belied her force of character and true role in the relationship.

She had a cyst between her eyebrows which Picasso said made her look like a unicorn. To hide it she combed her hair forward to the bridge of her nose and pulled her hats down to her eyes. She was under five-feet tall and when sitting her feet seldom reached the ground. She loved expensive gloves and took great care of her hands and nails, which she manicured daily, and she had a moustache which the food editor of House Beautiful, Poppy Cannon, in 1958 said made other faces seem nude by comparison. She had grey-green eyes a large hooked nose and an acute sense of smell and taste even though she was a heavy smoker.

Gertrude was large in girth though not in height. In her prime she weighed 200 pounds. She liked loose comfortable clothes with deep pockets. Pierre Balmain was a friend and he made clothes for her and Alice in the 1930s while he was still a student. He lined Gertrude’s baggy tweeds with mauve taffeta. She wore sandals even in winter, with fronts like the prows of gondolas, had a collection of waistcoats embroidered with flowers birds and the like, and for hats she wore an assortment of felt caps, straw lids, a cloche modelled on one that had belonged to Louis XIII which Alice thought would suit her, and a flower-bedecked one for high summer.

When Ernest Hemingway first met Gertrude in 1922 she reminded him of a northern Italian peasant woman with strong features, beautiful eyes, a mobile face and ‘lovely thick alive immigrant hair, which she wore up in the same way she had probably worn it in college’. But in 1926 Gertrude asked Alice to give her a haircut. Alice didn’t know how to go about it so the style became shorter and shorter, and the shorter it became the better Gertrude liked it. By the end of the session Gertrude didn’t have much hair left. Hemingway then thought she looked like a Roman emperor. ‘That was fine, if you liked your women to look like Roman emperors.’

Though neither Gertrude nor Alice ever wore trousers, their appearance could confuse. Gertrude, particularly in evening dress, was sometimes mistaken for something ecumenical – a bishop or a cardinal. At Christmas 1934, when they were staying with Gertrude’s cousin Julian Stein in Baltimore, one of his children aged three said of them that she liked the man but why did the lady have a moustache.

They first met in Paris on 8 September 1907. Alice heard bells ringing in her head when she saw Gertrude and thought that was proof she was in the presence of genius. She described Gertrude as ‘a golden presence burned by the Tuscan sun and with a golden glint in her warm brown hair’. She thought her beautiful, with a wonderful velvety contralto voice, an enormous sense of life and deep experience.

On Gertrude’s suggestion they walked alone together the next day in the Luxembourg Gardens and ate cakes in a patisserie off the boulevard St Michel. From then on, until Gertrude’s death thirty-nine years later, they were never apart. They never travelled without each other or entertained separately or worked on independent projects. Gertrude felt low in her mind if she was away from Alice for long. And Alice, writing about their relationship at the end of her own long life, said that from the moment they met ‘it was Gertrude Stein who held my complete attention, as she did for all the many years I knew her until her death and all these empty ones since then.’.

They became intractably related to each other a classic duo, as inseparable as Laurel and Hardy or Napoleon and Josephine perhaps. They called each other Pussy and Lovey in front of strangers. (Alice was Pussy.) They wrote notes to each other inscribed DD (Darling Darling) and YD (Your Darling). They regarded themselves as married. Alice often called Gertrude he, or her husband, or her Baby Woojums. She gave her a cut-out hand-coloured paper Annunciation in a gold-leafed frame inscribed MON EPOUX EST A MOY ET JE SUI A LUY (My husband is mine and I am his). Gertrude on occasion signed letters from them both ‘Gertrude and Alice Stein’. And in her love poems she made many a reference to the joys of conjugal life with Alice: ‘Little Alice B. is the wife for me’, she wrote, or

Tiny dish of delicious which

Is my wife and all

And a perfect ball.

Or

Your are my honey honey suckle

I am your bee.

Friends liked Gertrude’s pleasant handshake, huge personality, conversation, repose and easy laughter. Alice was sharp and more exacting company. Basket, their giant poodle, became a famous additional member of the family. Strangers commented on him. Mostly they said he looked like a sheep. Children called him Monsieur Basket or the dog in pyjamas. Gertrude said that of his ABCs he know only the Bs: Basket, bread and ball.

There was a moral base to the tryst between Gertrude and Alice. As a student at Harvard Gertrude had been entangled in a fraught triangular relationship with another woman. She wrote about the experience in her first novel QED. She described herself in the affair as trapped in ‘unillumined’ immorality and observed:

If you don’t begin with some theory of obligation anything is possible and no rule of right or wrong holds. One must either accept some theory or else believe one’s instinct or follow the world’s opinion.

Gertrude and Alice accepted the ‘theory of obligation’ and apart from the fact that they were both women their relationship fulfilled the codes and expectations of romantic love. Their life together became a paradigm of a good relationship. They fell in love, saw life from the same point of view and lived as a couple, with much emphasis on domestic harmony, until parted by death. They were happy and they said so. Alice said Gertrude was the happiest person she’d ever known. They were acerbic about the more fraught or varied private lives of many of their friends – Hemingway’s three wives, Picasso’s succession of women, Natalie Barney’s spirited affairs with lots of ladies.

They had much to unite them. Both were brought up in the San Francisco Bay area of California. Both were the daughters of European Jews who were first-generation immigrants to America. Both travelled in Europe when they were children and were in their teens when their mothers died. They had a Californian openness and hospitality, a cultural interest in Europe, a kind of pioneer courage. Though they lived in France they had little to do with the indigenous French. Sylvia Beach who ran the bookshop Shakespeare & Company said she never met French people at their apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus. They were staunchly patriotic about being American: ‘Americanism is born in me’ Gertrude said. They liked waving American flags at the end of the two World Wars. Though they left the States in the early 1900s and only once returned for a visit thirty years later, they regarded France as their adopted country and America as their native land. Their deepest point of agreement and the focus of much of their shared life was that Gertrude was a genius (‘Twentieth century literature is Gertrude Stein,’ Gertrude said) and that she and her genius must be served. This made for a perfect symbiosis, a harmonious division of labour. Gertrude liked to write, talk to people, drive the car, stay in bed until midday, lie in the sun, walk the dog, look at paintings and meditate about herself and life. Anything else made her nervous. Alice did the rest.

Alice was always fiercely busy. She could knit and read at the same time. She typed Gertrude’s manuscripts, dealt with household affairs, embroidered chair covers and handkerchiefs, dusted the pictures and ornaments, planned the menus, instructed the cook and the maid, washed the paintwork, arranged the flowers. In the country she did the digging planting and sowing. When she came to her own writing, after Gertrude’s death, it was reminiscences, menus and letters in a crisp acerbic style.

‘Alice B. Toklas is always forethoughtful,’ Gertrude wrote, ‘which is what is pleasant for me.’ A friend, Mabel Dodge, said to Alice in Italy in 1912, ‘I can’t understand you. What makes you contented? What keeps you going?’ Alice replied ‘Why I suppose it’s my feeling for Gertrude.’ More than twenty years later, when Gertrude as a celebrity toured America with Alice, Alice said that Gertrude was at home in America through her writing whereas she, Alice, was at home through Gertrude.

There was nothing demeaning in Alice’s servitude. She was the power behind the throne. Those who wanted to see Gertrude were first checked out by Alice and if Alice did not approve they were turned away. She believed herself to be descended from Polish nobility. As a girl she was taught to open a bottle of champagne cleanly at the neck and when sweeping up the day after a party to be careful about the diamonds in the dust.

Visitors to their Paris apartment found her frightening. Most of them wanted to see Gertrude. But behind Alice’s imperious façade was a streak of romantic daring. She left her home in San Francisco when she was thirty and took a chance on life in Paris. She had a passion for clothes, dangling jewels and hats adorned with flowers and feathers. On a train journey to Florence in the summer of 1908, troubled by the heat, she took off her cherry-coloured corset and threw it out of the window. She’d wanted to be a pianist and had studied music at Washington University, but thought her own talent fifth rate. So she promoted Gertrude’s instead. She was an excellent impresario. She managed and organised both their lives, shaped their fame and promoted their public image. It was she who selected the motto ‘Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose’ to appear in a circle on Gertrude’s stationery. Gertrude first used the words in a poem called Sacred Emily. Alice polished anecdotes about themselves until they became legend. Above everything she ensured that the quality of their daily life was orderly and agreeable.

Inherited money from the Stein estate allowed them to live in freedom and comfort. They chose to live in France when the cost of living was low. They never owned property. They rented their apartment in Paris and for fifteen years a large house in the Rhône valley. They ran a car from 1916 on and always had one or more servants. Their lifestyle was hospitable and extremely comfortable but not grandly affluent.

Gertrude’s true fortune was acquired through love – her collection of modern art bought for the most part before the First World War for not much money and before the success of the artists was established. The paintings, by Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne and others, were the treasures of her youth. She sold one or two of them reluctantly in later life to finance the publishing of her work or to buy food on the black market in the Second World War. She never adequately insured them or made an inventory of them. After she died, Alice suffered financial hardship to avoid selling any of them. She wanted them to go en bloc to a museum as Gertrude’s collection.

They were both well-settled in Paris long before the international literary community arrived there in the twenties and thirties. They were at the cultural heart of Paris for four decades through the revolutionary exhibitions of the Fauves and the cubists, the struggles of the innovative magazines of the twenties, the aspirations of the expatriate writers between the two World Wars. They were intrinsic to Paris at that time and became famous by virtue of being themselves. They attracted an audience wherever they went – in Charleston, Oxford or Avila. They were indomitable and a sight to be seen. They loved driving around in ‘Auntie’ their Ford car, looking at paintings and Roman ruins, eating delicious food, talking to everyone, making the best of where they were. For much of the time they seemed like two biddies on a spree. They took great delight in Gertrude’s success when it happened, late in their lives, and in spending the money she earned. They practised the art of enjoyable living in an unpretentious way. And they were so emphatically and uncompromisingly themselves that the world could do nothing less than accept them as they were.

Praise for Gertrude and Alice

Wonderfully entertaining. Not many biographies can make you laugh out loud. A real treat.

Time Out

Perfect: deadpan, brief and witty.

Independent

Souhami hits a true note in her ebullient introduction and sustains it throughout. Her narrative is terse and exact and her book, the story of two serious ladies, is very funny indeed.

Lucy Hughes-Hallett · Sunday Times

Like a good novelist Diana Souhami makes the characters in her book, major and minor, come alive. Hers is an exemplary biography in its scrupulous respect and affection for her subjects.

Cyra McFadden · San Francisco Examiner

An antidote for all those laundry lists they call biographies nowadays. Wonderfully diverting.

Mirabella

Souhami is deeply sympathetic to Gertrude and Alice. She is also witty and unsentimental.

Victoria Glendinning · Times

A brilliant and witty chronicle of one of the happiest marriages in modern literary history. Not only star-studded but light-filled.

John Richardson · Author of A Life of Picasso

Diana Souhami redefines and amplifies a remarkable relationship and a rich period of modern art. Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas created a world and Souhami takes us on an engrossing and illuminating journey through it.

May Sarton

Diana Souhami’s irresistibly charming Gertrude and Alice wins by a neck in a hectic field.

Philip Hensher · Daily Telegraph